Seaweed is one of those rare foods where the traditional wisdom and cutting-edge science meld together in really interesting ways, and there's a lot more going on than the typical "it's a good source of iodine" summary. Let me give you the fuller picture.

Seaweed has been a dietary staple across East Asia for millennia. In Korea, there's a longstanding tradition of new mothers eating miyeokguk (seaweed soup) postpartum for recovery. A practice that UConn researchers have noted reflects deep cultural knowledge about its nutritional properties.

Traditional Chinese Marine Materia Medica has catalogued seaweed's medicinal applications for centuries. Japanese coastal populations who eat seaweed regularly have long had notably lower rates of obesity and metabolic disease. An observation that modern epidemiology has now confirmed.This effect isn't just happening because of other dietary factors.

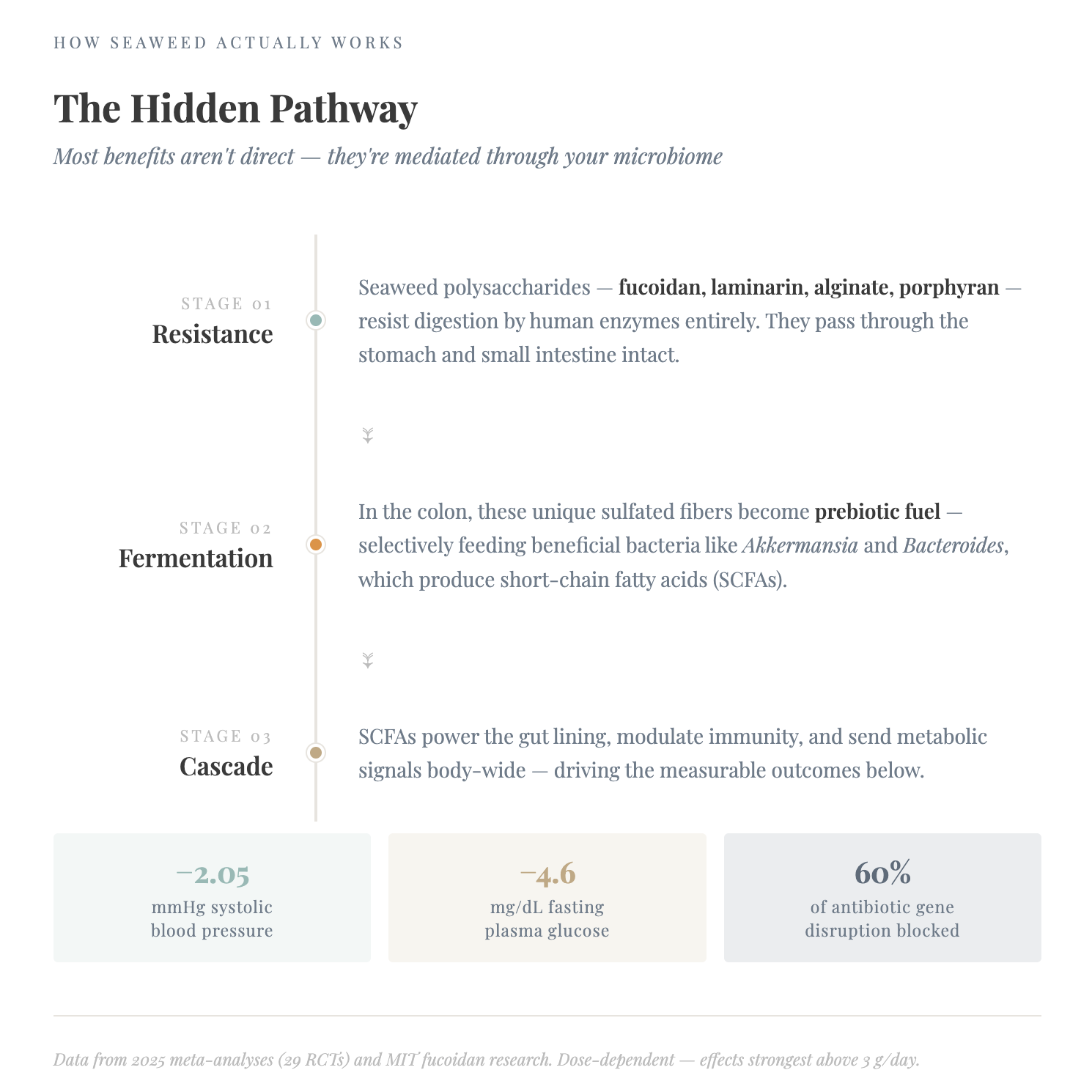

Cardiovascular and metabolic effects. A 2025 meta-analysis of 29 randomized controlled trials found that edible algae consumption lowered systolic and diastolic blood pressure by roughly 2 and 1.9 mmHg respectively, with doses above 3 grams per day producing reductions exceeding 3 mmHg.

That's a meaningful effect at a population level. Additional meta-analyses have confirmed that brown algae reduce LDL and total cholesterol, and improve glucose homeostasis by lowering fasting plasma glucose by about 4.6 mg/dL and postprandial glucose by 7.1 mg/dL.

UConn's mouse studies are particularly striking: mice fed a very high-fat, high-sugar, high-cholesterol diet alongside sugar kelp were protected against obesity and related diseases compared to mice eating the same unhealthy diet without kelp.

This is where it gets really interesting. Seaweed polysaccharides (fucoidan, laminarin, alginate, porphyran, ulvan) resist digestion by our own enzymes and reach the colon intact, where they function as prebiotic fuel for beneficial bacteria.

These unique polysaccharides improve beneficial bacterial populations and their production of short-chain fatty acids, which serve as the energy source for gastrointestinal epithelial cells, provide pathogen protection, and influence immune modulation.

A particularly exciting 2025 finding from MIT: researchers discovered that fucoidan provides broad-spectrum protection for gut microbiota against multiple classes of antibiotics, both in vitro and ex vivo. The mechanism is remarkable, fucoidan appears to bind to antibiotic molecules extracellularly, reducing their uptake by beneficial commensal bacteria.

It is exciting that this effect has been proven in a scientific study because this is potentially huge for anyone who needs antibiotics but wants to preserve their gut ecosystem.

It is also important to note that phlorotannins, fucoidan, and other seaweed polyphenols exhibit antioxidant and neuroprotective properties linked to reduced neuroinflammation and cognitive decline. This is a newer area but the preclinical data is accumulating steadily.

Brown, red, and green algae have fundamentally different bioactive profiles. Protein content ranges from 5–24% of dry weight in brown algae up to 47% in red species (News-Medical).

Iodine content varies by orders of magnitude. A 2025 Korean nationwide study found average iodine levels of 2,432 mg/kg dry weight in sea tangle, compared to less than 200 mg/kg in most red and green algae.

So the advice "eat seaweed for iodine" or "be careful of too much iodine" is meaningless without specifying the species.

Boiling or blanching can remove up to 90% of iodine content, and the bioavailability of iodine from seaweed is approximately 75% compared to iodide supplements. The Korean tradition of preparing seaweed in soups isn't just culinary preference — cooking it in liquid fundamentally alters the nutritional profile. Similarly, the Japanese practice of eating seaweed alongside cruciferous vegetables (which contain goitrogens that inhibit thyroid iodine uptake) looks increasingly like practical wisdom embedded in cuisine.

This is the most fascinating underappreciated angle. The bacterium Bacteroides plebeius, isolated from the intestines of regular Japanese seaweed consumers, produces a β-agarase enzyme specific to the agarose and porphyran components of red algae.

This enzyme isn't found in the gut microbiomes of populations that don't eat seaweed. The implication is that long-term seaweed-eating populations have gut bacteria that have literally acquired genes from marine microbes — a horizontal gene transfer that makes them better at extracting nutrition from seaweed. If you're new to eating seaweed, you may not get the same benefits as someone from a culture with generations of consumption, at least not immediately. Your microbiome needs time to adapt.

A Malaysian risk assessment found a hazard index of 4.38 for metal exposure from seaweed, exceeding WHO limits (News Medical). But this varies hugely by water source, species, and preparation. Hijiki is particularly problematic for arsenic.

The safety conversation hasn't kept pace with the enthusiasm, and UConn researchers linked above emphasize that studying health benefits and safety should proceed in parallel before making broad dietary recommendations.

The sulfate and carboxylic groups in seaweed polysaccharides promote higher fermentation rates in the gut, and the degree of sulfation influences both short-chain fatty acid production and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. This is a level of biochemical specificity that generic "eat more fiber" advice completely misses. These are structurally unique fibers that do things terrestrial plant fibers don't.

Seaweed acts more like a pharmacologically active food with dose-dependent, species-specific, and preparation-sensitive effects on cardiovascular, metabolic, gut, and possibly neurological health. Our partner Sunday Natural offers their seaweed supplements.

The most sophisticated way to think of it is as a prebiotic platform that feeds a specialized microbial ecosystem, which in turn mediates most of the downstream health effects.